In the early years of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, the Central Intelligence Agency harbored an uncomfortable secret about itself. The CIA had never really gained an espionage foothold on the streets of Moscow. The agency didn’t recruit there because it was just too dangerous for any Soviet citizen or official they might enlist. The recruitment process itself, from the first moment a possible spy was identified and approached, was filled with risk of discovery by the KGB, and if caught spying, an agent would face certain death. The CIA was also hampered for many years by fears of KGB deception to fool the West.

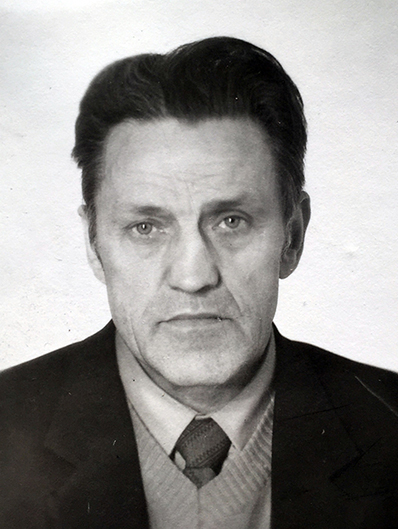

CIA headquarters in 1979. (AP photo)

The gas station in Moscow. (Courtesy of Valery Smychkov)

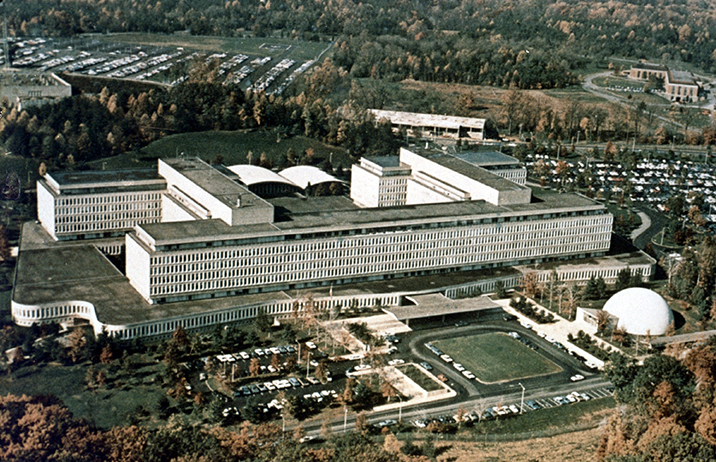

In January, 1977, the CIA station chief in Moscow, Bob Fulton, was filling up his car at a gas station used by diplomats and other foreigners. A Russian man walked up to him and spoke in English. “Are you American? I would like to talk to you.” The CIA ignored him at first, but he came back over and over again. He was Adolf Tolkachev, an engineer and specialist in airborne radar who worked deep inside the Soviet military establishment. In 1979, he became a spy for the United States with the code name CKSPHERE. He met with CIA officers twenty-one times over six years on the streets of Moscow, a city swarming with KGB surveillance, and was never detected.

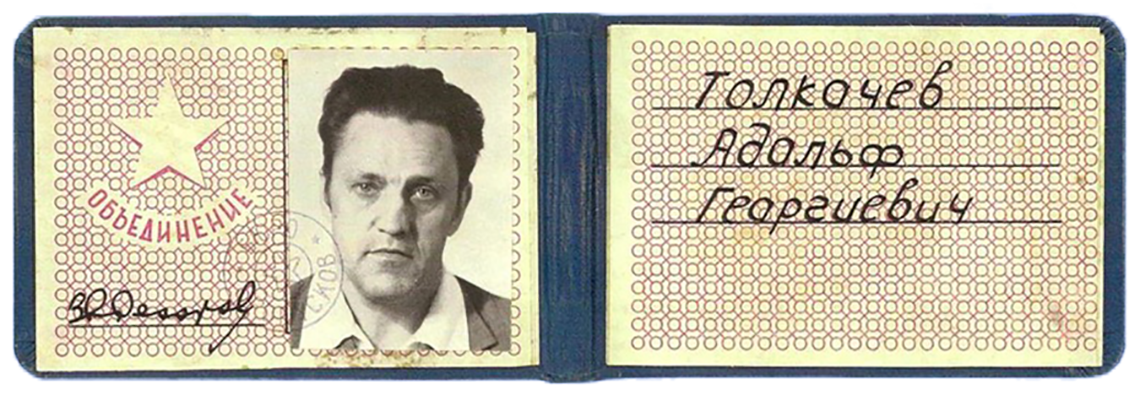

Adolf Tolkachev’s building pass. (Courtesy of H. Keith Melton and the Melton Archive)

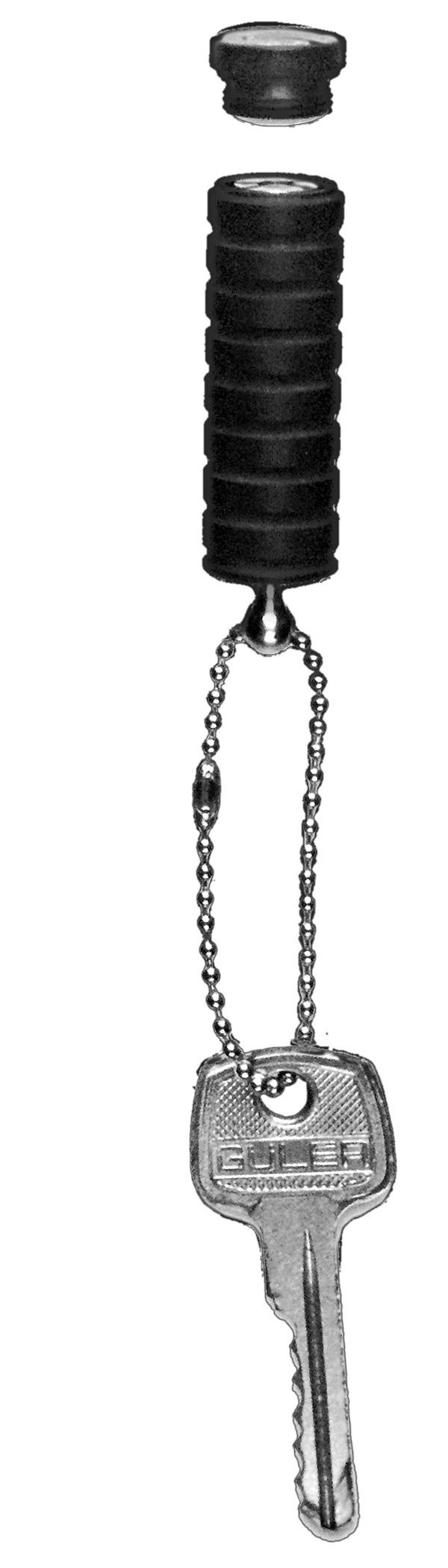

The Tolkachev operation involved some of the CIA’s most sophisticated technology at that time, including an advanced spy camera, a tiny wonder of optical engineering called the Tropel. However, Tolkachev preferred the simple reliability of a standard Pentax 35mm camera clamped to the back of a chair, with which he photographed thousands of pages of secret documents. The CIA also gave Tolkachev an advanced handheld electronic device for communications, but he much preferred to meet his CIA handlers in person.

The Pentax ME 35mm camera, like the one Tolkachev used. (Courtesy of Titrisol/Wikimedia Commons)

Above, the tiny Tropel camera concealed in a key fob. (Courtesy of H. Keith Melton and the Melton Archive)